The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe depicts a near-future in which death by old-age is the norm; almost all diseases have been eradicated, and it is only accidental death, or suicide, that usually ends a person’s life before the on-set of senescence. Occasionally, however, there is a rare disorder that cannot be cured, and such is the case with Katherine Mortenhoe, who is diagnosed with ‘Gordon’s Syndrome,’ and is told she has only four weeks to live.

Enter Human Destiny, a reality television show that offers the sufferings of the minority to the masses; the unscrupulous Vincent Ferriman, an executive at Human Destiny, wants to televise Katherine’s final twenty-eight days of life. And it is the intrepid reporter Rod (‘Roddie’) who is to bridge the gap between Katherine and the viewers. Rod has had cameras surgically attached to his retina; his eyes appear normal to others, but wherever he looks, he is filming (complete with sound). His trans-human enhancements have unfortunate side effect: his eyes are continuously perceiving, and he cannot sleep without drugs (hence the book’s alternate title, The Unsleeping Eye): Roddie cannot experience the dark; he carries a flashlight with him wherever he goes. Although the story is set in a future with significant medical advances and the possibility of cyborg technology, it has the texture of the 1970s British novel it is. The technological aspects are part of the set-up, but are not explained; this is not a hard science fiction novel, it is a character study of Katherine and Rod, two strangers who grow close in the midst of an emotionally charged situation. It is worth noting that Roddie’s sections are presented in first-person, while Katherine’s are written in third-person.

Enter Human Destiny, a reality television show that offers the sufferings of the minority to the masses; the unscrupulous Vincent Ferriman, an executive at Human Destiny, wants to televise Katherine’s final twenty-eight days of life. And it is the intrepid reporter Rod (‘Roddie’) who is to bridge the gap between Katherine and the viewers. Rod has had cameras surgically attached to his retina; his eyes appear normal to others, but wherever he looks, he is filming (complete with sound). His trans-human enhancements have unfortunate side effect: his eyes are continuously perceiving, and he cannot sleep without drugs (hence the book’s alternate title, The Unsleeping Eye): Roddie cannot experience the dark; he carries a flashlight with him wherever he goes. Although the story is set in a future with significant medical advances and the possibility of cyborg technology, it has the texture of the 1970s British novel it is. The technological aspects are part of the set-up, but are not explained; this is not a hard science fiction novel, it is a character study of Katherine and Rod, two strangers who grow close in the midst of an emotionally charged situation. It is worth noting that Roddie’s sections are presented in first-person, while Katherine’s are written in third-person.

The novel is well-written; and, although the book is bleak, misanthropic, and sand-blasted with moral outrage, it is also buoyed with a pinch of hope.

A few scenes didn’t work for me, but I’m nit-picking: it is an intriguing novel.

The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (The Unsleeping Eye) was adapted into a film titled Death Watch (by Bertrand Tavernier in 1980), staring Romy Schneider and Harvey Keitel; I haven’t seen the movie, but I think I’ll check it out (I always like to read the source novel before viewing the movie adaptation).

Monthly Archives: August 2013

Larry Niven and a Star Trek (TOS) animated episode

It’s at moments like this that I realize I’m not as cool as I think I am…

I was reading Larry Niven’s Ringworld (and enjoying it more than I thought I would, although it is strictly an idea book, and there is very little character development after the beginning sections). On page 11 of my copy I came across the following, and realized this was referring to a Niven short story that an animated Star Trek (TOS) was based on:

The puppeteer answered immediately, and without a tremor in its voice. “It was I who, on a world which circles Beta Lyrae, kicked a kzin called Chuft-Captain in the belly with my hind hoof, breaking three struts of his endoskeletal structure. I have need of a kzin of courage.”

Nessus, the puppeteer in the quote above, was referring to an event in a Larry Niven short story, The Soft Weapon, which was adapted into an animated Star Trek episode, The Slaver Weapon (1973). There is much more back-story in Niven’s short story (in Niven’s story the artifacts were created by the Tnuctip, who revolted against the Thrint , the so-called ‘Slavers,’ a telepathic race that ruled the galaxy through mind control). In The Soft Weapon, there is a human couple (replaced in the Star Trek episode with Nyota Ohura and Hikaru Sulu), a puppeteer (two-headed, three-legged, sentient beings, more intelligent than humans, but with an intelligence ruled by a ‘logical’ cowardice. In the Star Trek episode, Commander Spock is placed in the role of the puppeteer), and a spaceship with kzinti pirates (Niven’s kzinti look like rotund, eight-foot tall orange cats, and they are fierce, muscular warriors: their depiction in the Star Trek episode is done poorly, and their pink uniforms are a ghastly mistake).

Nessus, the puppeteer in the quote above, was referring to an event in a Larry Niven short story, The Soft Weapon, which was adapted into an animated Star Trek episode, The Slaver Weapon (1973). There is much more back-story in Niven’s short story (in Niven’s story the artifacts were created by the Tnuctip, who revolted against the Thrint , the so-called ‘Slavers,’ a telepathic race that ruled the galaxy through mind control). In The Soft Weapon, there is a human couple (replaced in the Star Trek episode with Nyota Ohura and Hikaru Sulu), a puppeteer (two-headed, three-legged, sentient beings, more intelligent than humans, but with an intelligence ruled by a ‘logical’ cowardice. In the Star Trek episode, Commander Spock is placed in the role of the puppeteer), and a spaceship with kzinti pirates (Niven’s kzinti look like rotund, eight-foot tall orange cats, and they are fierce, muscular warriors: their depiction in the Star Trek episode is done poorly, and their pink uniforms are a ghastly mistake).

Apparently, Larry Niven was asked to write an episode for the animated series, but had difficulties creating a story that satisfied the producers; Gene Roddenberry suggested adapting The Soft Weapon, and the rest is history.

When I watched the Star Trek episode with my daughter, I knew it was based on a Larry Niven story, but the details were foggy; it filled my inner geek with joy when I came across the passage in Ringworld serendipitously, thereby releasing the memory (with some help from google). I was also struck by the delicate balance between cool and geek ; alas, I’m quite proud of my inner geek…

Retrospeculative View, 1966

Some of the short fiction published in 1966:

Some of the short fiction published in 1966:

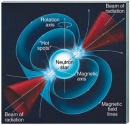

Neutron Star, by Larry Niven, which won the Hugo Award for short story

Bookworm, Run!, by Vernor Vinge

For a Breath I Tarry, by Roger Zelazny

The Last Castle, by Jack Vance, which won the Hugo Award for novelette and the Nebula Award for novella (I suppose it was considered either a long novelette or a short novella).

We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, by Philip K. Dick. This story was the inspiration for the two Total Recall movies (1990 and 2012).

Light of Other Days, by Bob Shaw

Man In His Time, by Brian W. Aldiss

Call Him Lord, Gordon R. Dickinson, which won the Nebula Award for novelette

The Secret Place, Richard McKenna, which won the Nebula Award for short story

.

Some television shows first broadcasted in 1966:

Star Trek (1966-1969). In retrospect, the most forward-thinking element about the show was the group that worked together with the white-bread males: a black woman (black actors of either sex were rarely observed on TV at the time), a man of Japanese descent (also rarely seen, except as a white man with makeup), and a Russian (during the cold war!). The creator, Gene Roddenberry, originally wanted the second-in-command to be a woman, but that was too progressive and frightening for the conservative money-men. It was a wonderful mix; but, for me, it was the Spock character (played by Leonard Nimoy) — the half-human, half-Vulcan — that made for interesting developments.

Batman (1966-1968), the live-action, campy, tongue-in-cheek adaption of the dark, brooding comic book hero. The TV show tickled the fancy of many, but annoyed some comic book aficionados.

The Marvel Super Heros (September — December 1966), an animated showcase of five Marvel Super Heros: Captain America on Monday, The Incredible Hulk on Tuesday, the Invincible Ironman on Wednesday, The Mighty Thor on Thursday, and Prince Namor the Sub-Mariner on Friday. The series was in colour, but the animation was minimalistic, produced by a process referred to as xerography, which is much more mundane than the name implies: photocopies of comic images were used and the only ‘animation’ was lip movement, with a rare shift of an arm or leg (some segments had animated silhouettes).

.

Some of the movies of 1966:

Batman: The Movie, based on the television show (see above).

Persona, a Swedish film directed by Ingmar Bergman. The movie is considered to be a masterpiece, and Bergman called it one of his most important films. It is a difficult film to describe, but it is certainly psychological and minimalistic, and Bergman utilized intriguing cinematography. It has been interpreted in many different ways, but is possibly best labelled as an avant-garde horror story.

Fantastic Voyage, starring Stephen Boyd, Raquel Welch, Edmond O’Brien, and Donald Pleasence. Based on a story by Otto Klement and Jerome Bixby. A crew is shrunk down to a miniature size in order to enter a man’s body and save his life (he is a scientist with secret information, but he is in a coma and he has an inoperable brain clot that can only be cured by the miniature team from inside). I mistakenly thought Isaac Asimov wrote the story, but he wrote a novelization of the screenplay; Asimov’s novelization was published before the movie was released, and the general public (me included) assumed that his novel inspired the film.

.

Some of the novels of 1966:

The Witches of Karras, by James H. Schmitz, his most enduring work of fiction. The novel is an amalgamation of science fiction and fantasy, and can probably best be pigeonholed in the genre of space-opera. The protagonist, Captain Pausert, becomes involved with a trio of young witches, who are sisters (in descending order of age, Maleen, Goth, and the Leewit), and the captain’s life branches off in unexpected directions. After an initial adventure that includes a visit to the witch’s home planet and troubles with various government organizations (presented as a novella in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, volume 2B), Pausert and Goth journey the galaxy sashaying from one humorous adventure to the next. A fun, minor speculative classic, best enjoyed for the first time at a young age.

World of Ptavvs, by Larry Niven. The novel is set in Niven’s ‘Known Space’ universe. I enjoyed Niven’s novels when I was younger (particularly Ringworld); he writes about interesting phenomena and aliens, but he is not an elegant writer. I read World of Ptavvs many years ago and I needed to search the web for a synopsis to patch the holes in my memory. A statue is found at the bottom of the ocean, but the statue is actually a Thrint in a stasis field. The Thrint are a telepathic, alien species that — many hundreds of years before the events in the novel take place — ruled the galaxy through mind control: the subjugated species rebelled, and the Thrint’s control was broken, although at a catastrophic cost to the rebellious sentient species. The plot is basically a struggle between the human that discovered the Thrint at the bottom of the ocean, and the Thrint. Interestingly, a Ptavv is a Thrint without telepathic abilities, and the Wolrd of Ptavvs, such an exotic sounding planet, is Earth.

Rocannon’s World, by Ursula K. Le Guin. This was Ms. Le Guin’s first published novel. The novel’s prologue is an earlier short-story, Semley’s Necklace (1964), which has been extrapolated into a short novel, which, although not as remarkable as her later fiction output (in particular, The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed), is an interesting glimpse into the early work of a developing talent.

Flowers for Algernon, by Daniel Keyes, which won the Nebula Award (a tie with Delany’s Babel-17). This is an expanded form of the classic 1959 short story (which won the Hugo Award). I enjoyed the novel, but prefer the short story version: I don’t think the expanded story adds anything significant, and there were a couple of ‘new’ sections that I thought could have been excised.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert A. Heinlein, which won the Hugo Award. This is probably my favorite Heinlein novel (and is his best title); although, for me, his writing hasn’t aged well: his prose is smooth, but seems pulpy to me now and I have a difficult time reading his works. His novels tended to be political, and this novel was no exception, though the politics add to the plot, rather than detracting from it (as I found was the case in Starship Trooper). The most interesting character is the sentient computer, Mike. This is a typical Hugo Award novel; interesting ideas and fun to read, but not necessarily written with literate qualities.

And my choice for Retrospeculative novel of 1966 is…

Babel-17, by Samuel R. Delany, winner of the Nebula Award (a tie with Keye’s Flowers for Algernon). This is an early Delany novel that explored linguistics, sociology, and psychology. Like a few other science fiction novels of the time (e.g.: Jack Vance’s The Languages of Pao), Babel-17 examines the idea that linguistic construction affects the speaker’s perception of reality (linguistic relativity, generally know as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism. The theory has since been debunked: language has a slight influence on perception, but nothing like that imagined in the novel; nevertheless, the idea works well in the confines of the story). The title refers to a codified language that is being used for sabotage in an interstellar war. The protagonist, Rydra Wong, is a poet with a genius-level aptitude for languages. Some of her poems are included within the novel: these poems, which add texture and realism to the work, were written by Marilyn Hacker, who was Delany’s wife at the time. Delany is one of my favorite science fiction authors and this is an interesting book, but the ending felt rushed, and the novel was a bit uneven compared to his best books; nevertheless, Babel-17 is a remarkable work, well worth perusing.

Babel-17, by Samuel R. Delany, winner of the Nebula Award (a tie with Keye’s Flowers for Algernon). This is an early Delany novel that explored linguistics, sociology, and psychology. Like a few other science fiction novels of the time (e.g.: Jack Vance’s The Languages of Pao), Babel-17 examines the idea that linguistic construction affects the speaker’s perception of reality (linguistic relativity, generally know as the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, or Whorfianism. The theory has since been debunked: language has a slight influence on perception, but nothing like that imagined in the novel; nevertheless, the idea works well in the confines of the story). The title refers to a codified language that is being used for sabotage in an interstellar war. The protagonist, Rydra Wong, is a poet with a genius-level aptitude for languages. Some of her poems are included within the novel: these poems, which add texture and realism to the work, were written by Marilyn Hacker, who was Delany’s wife at the time. Delany is one of my favorite science fiction authors and this is an interesting book, but the ending felt rushed, and the novel was a bit uneven compared to his best books; nevertheless, Babel-17 is a remarkable work, well worth perusing.

The Difference Engine, by William Gibson and Bruce Sterling

The Difference Engine (1990) is an alternate-reality Steampunk novel; a classic that was ahead of its time, and a seminal tome in the genre. It investigates what would have occurred if Charles Babbage had succeeded in creating a working mechanical computer in the mid-19th century; in the confines of the novel, the result is that Britain launches into the Industrial and Information Revolutions at the same time.

The Difference Engine (1990) is an alternate-reality Steampunk novel; a classic that was ahead of its time, and a seminal tome in the genre. It investigates what would have occurred if Charles Babbage had succeeded in creating a working mechanical computer in the mid-19th century; in the confines of the novel, the result is that Britain launches into the Industrial and Information Revolutions at the same time.

As I began my journey through the book I had doubts that Babbage’s computer would have been effective enough for the blossoming of the Information Age — his computer would have been incredibly slow, and certainly not robust enough to be of practical use — but the story was intriguing enough to warrant suspension of disbelief, and the authors were clever enough to forgo any explanation of how the invention was perfected: it is presented as a fait accompli.

The novel is predominately populated with historical individuals and characters from Sybil, or The Two Nations, a novel by Benjamin Disraeli, who also appears as a character in The Difference Engine. Disraeli’s novel depicts the appalling life of the working-class in the mid-19th century. The authors’ research is inspiring, but at times the novel reads like a history book; fascinating, but a bit of a slog. The book is idea driven, and I prefer a character driven story. I recommend the on-line “Difference Dictionary” (provided by Eileen Gunn), which is a useful reference while reading the novel. If you’re really curious, you might also like to peruse an essay by Elisabeth Kraus: “Gibson and Sterling’s Alternative History: The Difference Engine as Radical Rewriting of Disraeli’s Sybil”

The novel is presented in a series of episodes, with three main characters: Sybil Gerard, a prostitute and daughter of a revolutionary Luddite; Edward Mallory, an adventurous paleontologist; and Laurence Oliphant, a journalist/spy. Each of the main characters is interesting; but, as a reader, I was never fully engaged with any of them (I found some of the Mallory sections protracted and somewhat tedious). Each received an interesting initial character sketch, but they weren’t plumbed to a depth sufficient for an emotional attachment; interestingly, this may have been the authors’ intent.

The ending made the journey worthwhile and shed some light on why the book’s writing style was used. I don’t think I will ever re-read the book; but, after knowing who the narrator is, a second reading might be more enlightening. I won’t reveal the narrator, although I don’t think it would ruin the story (I think it would actually add to the story), I’ll just point out that the book isn’t divided into chapters, but into six Iterations (from Merriam-Webster.com: a procedure in which repetition of a sequence of operations yields results successively closer to a desired result and/or the repetition of a sequence of computer instructions a specified number of times or until a condition is met). There is also a final section, a Modus, and an interesting Afterward by the authors.

The Difference Engine is a well researched, fascinating book, but there are many sections — particularly in the middle — I struggled through. I’m glad I persevered through to the end, but I can’t wholeheartedly recommend the book. Some, no doubt, will adore it, but the novel won’t appeal to everyone’s taste.

.

.

.

Retrospeculative View, 1965

1965 was the inaugural year for the Nebula Awards, which I’ve always considered to be an award for literate and experimental science fiction works. In comparison, I’ve assumed that the Hugo Award is generally presented to more popular works. It should be interesting to see if my theory bears fruit as the Retrospeculative years roll along on this blog (it doesn’t appear to be the case in 1965: both the Nebula and the Hugo were awarded to the same novel and the same short story). 1965 was a banner award year for Roger Zelazny, who won two Nebula Awards (for best Novella and best Novelette) and a Hugo Award (for best novel, in a tie with Frank Herbert’s Dune)…

1965 was the inaugural year for the Nebula Awards, which I’ve always considered to be an award for literate and experimental science fiction works. In comparison, I’ve assumed that the Hugo Award is generally presented to more popular works. It should be interesting to see if my theory bears fruit as the Retrospeculative years roll along on this blog (it doesn’t appear to be the case in 1965: both the Nebula and the Hugo were awarded to the same novel and the same short story). 1965 was a banner award year for Roger Zelazny, who won two Nebula Awards (for best Novella and best Novelette) and a Hugo Award (for best novel, in a tie with Frank Herbert’s Dune)…

Some of the short stories:

Harlan Ellison’s Repent, Harlequin! Said the Ticktockman, the Hugo and Nebula Award winner for short story.

Brian Aldiss’ The Saliva Tree, the Nebula Award winner for best novella (tie)

Roger Zelazny’s He Who Shapes, the Nebula Award winner for best novella (tie)

Roger Zelazny’s The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth, the Nebula Award winner for best novelette

Philip José Farmer’s Day of the Great Shout,

Poul Anderson’s Marque and Reprisal

Fritz Leiber’s Stardock.

.

New television shows in 1965:

Lost in Space, a forgettable TV show that included a ‘Class M-3 Model B9, General Utility Non-Theorizing Environmental Control Robot’ (reminiscent of Robby the robot from Forbidden Planet, et al.) that often enunciated: “Danger, danger,” while waving its articulated arms and flashing lights in its chest region. An equally forgettable movie version was made in 1988, starring, among others, Matt LeBlanc (Joey, from the TV sitcom Friends), Gary Oldman and William Hurt.

Thunderbirds, a British science fiction television series that used AP Films’ style of marionette puppetry they christened Supermarionation. The Thunderbirds were a fleet of five types of vehicle-machines: a rocket plane, a rescue aircraft, a spaceship, a submersible, and a space station.

.

Some of the movies released in 1965:

The War Game depicted a fictionalized, nuclear war between Russia and Britain. The show was intended for television, but the BBC decided it was too graphic and frightening. The show, presented in the form of a news commentary, had a limited release in cinemas and won an Oscar for Best Documentary Feature (I’m a bit confused about this: wasn’t the film fiction?).

Alphaville (subtitled une étrange adventure de Lemmy Caution). Lemmy Caution is a private detective in a futuristic city on an alien planet. The city’s despot has forbidden love and self-expression. A curious movie that blended science fiction and Film Noir.

Die, Monster, Die! A minor B-Horror classic, apparently very loosely based on H.P. Lovecraft’s 1927 story The Colour Out of Space. Stephen Reinhart (played by Nick Adams) visits his fiancé’s father (played by Boris Karloff), a scientist who is confined to a wheelchair and who has discovered a radiation-emitting meteor that transforms things.

.

And a sampling of the speculative novels of 1965:

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, by Philip K. Dick. I’ve enjoyed a couple of PKD’s novels; this isn’t one of them, but the common perception seems to be that it is one of his better books. It examines similar themes to his other novels, including questions about ultimate reality, paranoia and identity; but, to me, the novel breaks no new ground and reads like PKD’s typical adrenaline-charged pulp, filled with cardboard characters that are indistinguishable from each other. Perhaps this is what the author intended, but it didn’t work for me. In case you’re interested, Palmer Eldritch’s three stigmata consist of an artificial arm, steel teeth, and electronic eyes.

The Black Cauldron by Lloyd Alexander, the second book in The Prydain Chronicles, a high fantasy series inspired by Welsh mythology. The novel was a Newbery Honor book, short-listed for the year’s “most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” An animated Disney movie — loosely based on the story — was released in 1985, but it was a commercial failure at the box office.

God Bless you, Mr. Rosewater, by Kurt Vonnegut. I haven’t read this novel and I probably never will (too many books, too little time). I’m sure it’s enjoyable, but I’ve read what I think is a good representation of Vonnegut’s works (Player Piano, The Sirens of Titan, Cat’s Cradle, Slaughterhouse Five, and several short stories). In his book Palm Sunday (Chapter 18, The Sexual Revolution), Vonnegut graded his works — as a comparison with himself, not others — and gave God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater an ‘A’ grade, so he obviously thought it was one of his better novels (three other novels — The Sirens of Titan, Mother Night, and Jailbird — received an ‘A’ grade, and only Cat’s Cradle and Slaughterhouse Five received a higher mark, an ‘A+’).

…And Call Me Conrad (alternate title: This Immortal) by Roger Zelazny. I haven’t read this novel, but I should probably read more Zelazny because I think that his short story A Rose for Ecclesiastes is exceptional. …And Call Me Conrad shared the Hugo Award with Dune, but certainly hasn’t shared the lasting popularity of Frank Herbert’s book. Zelazny is probably better known for his Chronicles of Amber series and his novel Lord of Light (which didn’t appeal to me, but I seem to be in the minority). The novel was serialized as …And Call Me Conrad, and novelized as This Immortal, apparently with the restoration of many of the portions that were cut for serialization.

And my choice for Retrospeculative novel of 1965 is…

Dune, by Frank Herbert, which won both the Hugo Award (a tie with Zelazny’s …And Call Me Conrad) and the inaugural Nebula Award, and is a classic, multi-layered science fiction novel, bursting with politics, religion, ecology (of the desert planet Arrakis), and technology. The setting for action mostly takes place on the desert planet Arrakis, the source of an incredibly valuable commodity called mélange, or ‘spice.’ Separate factions vie for control of mélange, and the maneuverings, betrayals, and acts of heroic loyalty are examined as the plot unfolds. I found the story fascinating and impressive when I first read it, but I now find the writing a bit unrefined; nevertheless, it is a worthy classic of the genre. Herbert wrote five sequels, and several other sequels and prequels were co-authored by Kevin J. Anderson and Brian Herbert (Frank Herbert’s son). The original Dune novel towers above the rest.

Dune, by Frank Herbert, which won both the Hugo Award (a tie with Zelazny’s …And Call Me Conrad) and the inaugural Nebula Award, and is a classic, multi-layered science fiction novel, bursting with politics, religion, ecology (of the desert planet Arrakis), and technology. The setting for action mostly takes place on the desert planet Arrakis, the source of an incredibly valuable commodity called mélange, or ‘spice.’ Separate factions vie for control of mélange, and the maneuverings, betrayals, and acts of heroic loyalty are examined as the plot unfolds. I found the story fascinating and impressive when I first read it, but I now find the writing a bit unrefined; nevertheless, it is a worthy classic of the genre. Herbert wrote five sequels, and several other sequels and prequels were co-authored by Kevin J. Anderson and Brian Herbert (Frank Herbert’s son). The original Dune novel towers above the rest.

Bridge of Birds, by Barry Hughart

I just finished re-reading The Bridge of Birds and thoroughly enjoyed it: I first read the novel in 1985 (it was subtitled A Novel of an Ancient China That Never Was). I wanted to re-read the book, but didn’t really want to root-through my storage to find the ‘mass market paperback’, so I bought a used hardback copy of The Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox from Indigo (nice book, I think it was < $15 including shipping), which also contains the other two novels Barry Hughart wrote (also Master Li and Number Ten Ox stories: The Story of the Stone, and Eight Skilled Gentlemen). The title, Bridge of Birds, is apparently derived from the Cowherd and Weaver Girl myth (Que Qiao, ‘the bridge of magpies’). Other myths, poems, epics, historical events, and a taste of Taoism, are woven into the tale.

I just finished re-reading The Bridge of Birds and thoroughly enjoyed it: I first read the novel in 1985 (it was subtitled A Novel of an Ancient China That Never Was). I wanted to re-read the book, but didn’t really want to root-through my storage to find the ‘mass market paperback’, so I bought a used hardback copy of The Chronicles of Master Li and Number Ten Ox from Indigo (nice book, I think it was < $15 including shipping), which also contains the other two novels Barry Hughart wrote (also Master Li and Number Ten Ox stories: The Story of the Stone, and Eight Skilled Gentlemen). The title, Bridge of Birds, is apparently derived from the Cowherd and Weaver Girl myth (Que Qiao, ‘the bridge of magpies’). Other myths, poems, epics, historical events, and a taste of Taoism, are woven into the tale.

Master Li Kao is an eminent scholar “with a slight flaw in his character,” and Number Ten Ox (aka Lu Yu) is a young man from the village of Ku-fu (he is a rather muscular young man, and he is the narrator of the tales). The children of Ox’s village are poisoned, and the only antidote is contained in the essence of the Great Root of Power. Ox and Master Li go on an epic quest, but their goal appears to be entwined with an ancient tale of intrigue and murder.

Hughart had difficulty completing the manuscript, but found inspiration while reading The Importance of Understanding by Lin Yutang (he refers to the book within the novel).

The story is presented in a whimsical style; it begins slowly, but the author skillfully paints a wonderful picture. A good summer book; relaxing, pleasant, and not intellectually challenging…a perfect escape.

Hughart had planned to write seven Master Li and Number Ten Ox tales, but he had some ‘issues’ with his publisher and only completed three.